In an earlier article, we talked about ad hoc project management and how several Oil & Gas manufacturers lack a formal project management framework. These manufacturers rely primarily on “Hero” project managers to successfully deliver their projects. In other words, they’re at the mercy of the random, heroic efforts of a few key people in lieu of a repeatable and predictable framework that’s formally used by the entire organization. Ad hoc project management is costly and frustrating for most manufacturers and their customers. We know because we’ve lived it.

What happens when these same manufacturers develop new products? Having been involved in several complex drilling systems product development projects over the years, we’ve experienced the good the bad and the ugly. Our experience—and other sources1—tells us that an ad hoc, or informal approach to new product development is very costly and painful.

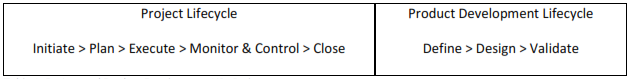

Any type of product development occurs under the auspices of a project, whether it’s formally called a “project” by the organization or not. A “project” is defined as a unique endeavor undertaken to deliver a unique product, service or result. Let’s assume that a manufacturer wants to develop a new product. This new product will be unique and will be the output, or deliverable, of a unique undertaking called a project. The project and the product development each have their own distinct lifecycles, simplistically shown in Table 1:

Table 1: Project and Product Development Life Cycles

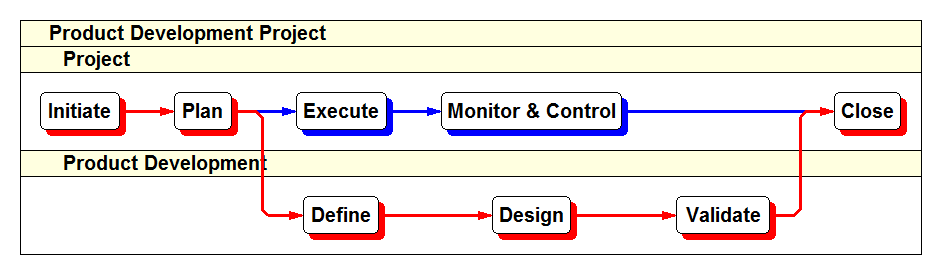

Note that the product development lifecycle is actually a subset of the project’s lifecycle. At a very high level, a network diagram for a product development project might look like this:

Figure 1: Product Development Network Diagram

Notice that the project delivers a validated new product. The standard production, test, delivery, installation and commissioning of the product(s)—as well as the field reporting, service and aftermarket support of the product(s)—might be a part of separate project(s) and/or operations.

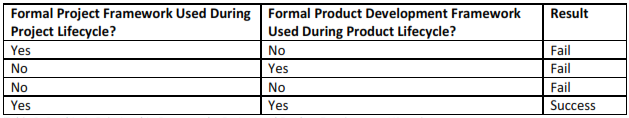

Over the years we’ve had to learn the hard way that even though they have their own distinct life cycles, the relationship between the project and product development are symbiotic: each lifecycle lives or dies based on the success or failure of the other’s lifecycle (see Table 2).

Table 2: Symbiotic Relationship Between the Project and Product Development Lifecycles

Success means consistently being within the planned product development cost and schedule and failure means consistently exceeding the planned cost and schedule. Having planned cost and schedule criteria and then consistently meeting that criteria implies that your organization uses formal project and product development frameworks. Another way to look at is, success means being predictable. Conversely, failure means being unpredictable.

For us, some aspects of a formal product development framework include:

- a project charter that clearly identifies the business case

- stakeholders identified, their requirements listed and prioritized

- clearly defined inputs and outputs, Define phase

- clearly defined inputs and outputs, Design phase

- clearly defined inputs and outputs, Validation phase

- formal change management process

It’s important to note that success doesn’t mean just sticking to a schedule or budget for the sake of meeting key milestones. Development work is iterative, plans can change. Blindly sticking to a linear milestone schedule “no matter what” can lead to disaster2. Notice the emphasis in the bulleted list above is on “clearly defined inputs and outputs”. We’re talking about adequate planning and planning can’t be rushed. In our experience, planning at the systems engineering and integration level is the key to enjoying lower overall product lifecycle costs. But unfortunately, it’s planning that usually gets the short shrift when it comes to projects and product development in the Oil & Gas manufacturing industry. Why? We think one of the main reasons is that we, as humans, have a lot of cognitive biases. One of our biases is to want to take immediate action and/or appear to be doing something useful when we’re confronted with uncertainty or risk. Psychologists call this the “Action Bias”3. Having a formal framework for projects and product development helps eliminate this uncertainty and perceived (if not real) risk and thus the urge to take unnecessary action.

When it comes to planning up front and having a well-defined framework to work to, consider what NASA has to say about escalating product development project costs4:

“If the cost of fixing a requirements error discovered during the requirements phase is defined to be 1 unit, the cost to fix that error if found during the design phase increases to 3-8 units; at the manufacturing/build phase, the cost to fix the error is 7-16 units; at the integration and test phase, the cost to fix the error becomes 21-78 units; and at the operations phase, the cost to fix the requirements error ranged from 29 units to more than 1500 units.”

Just like with project management, we’re not suggesting a one-size-fits-all approach to product development. But again, we do advocate having a formal approach (i.e. a framework). And that approach needs to be defined and formalized before the project starts.

© 2015 by LinRich Solutions, LLC. All rights reserved

1See Specification-Driven Product Development, by Edward K. Bower and System Engineering Planning and Enterprise Identity, by Jeffry O. Grady.

2Six Myths of Product Development (Harvard Business Review, May 2012 Issue), by Stefan Thomke and Donald Reinersten.

3The Art of Thinking Clearly, by Rolf Dobelli

4Error Cost Escalation through the Project Life Cycle, NASA Johnson Space Center